Let’s start off with the obvious. OERs, open textbooks, and other open content have never had more public support or momentum. State governments, universities, and organizations are all upping their openness game in an effort to combat the rising costs of education.

Here are just a few examples of the open learning content momentum:

- California senator will introduce open textbook legislation

- Utah State Office of Education will develop and support open textbooks in key curriculum areas

- Washington State passes legislation to develop a library of high-quality, openly licensed K-12 courseware that

8 is aligned with tCommon Core standards://apps.leg.wa.gov/ - OpenStax will offer free course materials for five common introductory classes

And this is only the tip of the open learning content iceberg. In addition to the plethora or organized OER and open textbook projects there are also thousands of individual instructors and teachers creating openly licensed learning content.

Yet, even the movement’s biggest proponents know that simply showing up with free content won’t lead to broad usage in the K-12 or Higher Education sectors. David Wiley points out that open content currently has no answer for “the coming wave of diagnostic, adaptive products coming from the publishers.” Others have made similar arguments and talk about the silted nature of open learning content. In my new book, The Future of Learning Content, I list several shortcomings that the OER and open textbook communities need to overcome in order for open learning content to revolutionize the US education landscape:

- A lack of discoverability of open learning content across the many disconnected silos

- A lack of proper, open mechanisms for aggregating and delivering OERs and open textbooks in cohesive and usable packages;

- An unevenness in quality across the pen learning content spectrum;

- An inconsistency in quality of open learning content.

The bottom line isn’t that we have a shortage of open learning content but rather that we haven’t yet figured out how to make it easy for instructors to use. In other words, we need to expand our efforts beyond making open learning content to making it useful.

Coolness and adaptive assessment packages aside, the real attraction of commercial publisher content is that it is easy. It’s easy to find conformation on commercial textbook products and their ancillary packages. It’s easy to adopt commercial textbook products and get them into the hands (or on the devices) of our students. It’s easy to use these products in our classrooms, our LMS platforms, and in our mobile initiatives.

Do we really want open learning content to have a broad impact in US education? If so, we need to invest in initiatives that focus on discoverability, customization, and ease of adoption and and use. The future of open learning content depends on this investment.

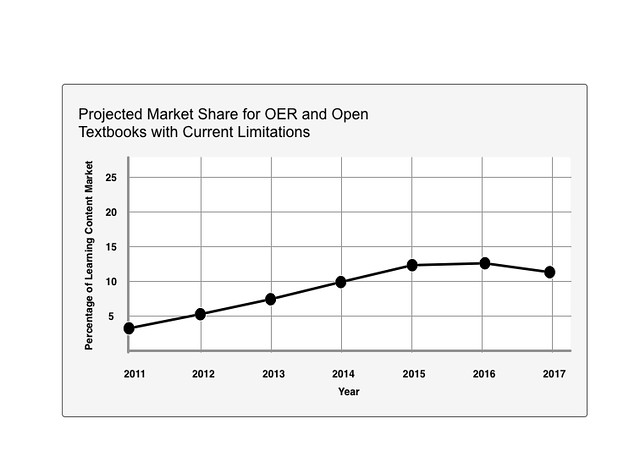

In fact, as we look at current projections around the popularity and market penetration of OERs and open textbooks in the US, we’re really looking at two possible futures. In one future we will continue creating lots of open learning content in disconnected silos and without the necessary mechanisms for making it easy to adopt and use. In this future the use of OERs and open textbooks will continue to grow through 2015 but will decline precipitously after that point in time.

In an alternative future, we will invest in making open learning content as easy to discover and use as commercial learning content. The result of this investment will be continued and aggressive growth in the adoption and use of open learning content.

Yes, we will also need to invest in those cool features and adaptive assessment packages. But price will be the driving factor for a few years to come and if we can add “easy” to “free” we just might have a huge winner on our hands.

Rob – nice post, and welcome to e-Literate. I think you’re right about the need to make OER easy to discover, access and use. Also agree about need to invest.

One question I have is whether you think OER can overcome the sales channel advantages of publishers without having for-profit service companies involved. Discoverability and access are activities that faculty and others must do, where the publishers have huge sales forces that go to the faculty and make it easy for them to simply choose. By way of analogy, I don’t think Moodle and Sakai would have had the same market share penetration without MoodleRooms, RemoteLearner and rSmart, for example. Does OER need the same model for real adoption and change to occur?

Phil,

I think your observation about the need for commercial partnership is accurate. Michael hinted at this in his post on OER funding a while back. This is definitely something that needs to evolve int he open learning content space.

With regards to publisher sales forces, I think open content initiatives must combat these but the real issues are around brand awareness (no sales force needed, necessarily) and the right automation tools that can make instructor life easier (they won’t have to talk to sales reps) and push personalized, turnkey solutions to instructors.

Interesting post.

Whilst I support OER and the whole movement, I do have some critical views related to it’s sustainability and being mainstream – what will happen when those funded projects finish? With the exception of the very large projects such as MIT et. al, is there a business model to warrant engagement with OER?

I think OER happens on a couple of different layers – staff and students, and givers and takers. Post funding, I don’t see a massive amount of givers, so wonder if the movement is sustainable.

I’ve shared my thoughts here;

http://scieng-elearning.blogspot.com/2012/03/is-oer-mainstreamed-and-sustainable.html

@reedyreedles

Thanks for the thoughts, Peter. My short response is that OER (I’m defining broadly as all openly licensed learning content) is already abundant enough that sustainability is much less about content creation than it is about content aggregation, curation, and promotion. It’s not about making content but about making it more useful. This is particularly true since a majority of OER content is actually created by individuals outside of formal funding. This, in turn, creates an even greater diffusion of OER content (even beyond the current silo repositories). In this sense, I believe that it is not only sustainable but it is also not extremely expensive to achieve that sustainability.

As to business models, there are plenty. In particular, we should look to the many premium learning content providers who make use of OER content as “free” supplemental material. These providers spend a significant amount of money each yer to curate free content (which is cheaper than creating new content). Services that could offset that expenditure would be an easy sell.

Sorry, I was a bit short in my response and just linked to my post.

Whilst I am very much ‘for’ the movement, I have been thinking about the movement reaching mainstream. In order for it to reach mainstream then the majority of staff have to be involved in the movement. My research (and other research in the UK) highlight that the majority of staff are not engaging in the movement. They are sharing content with colleagues informally, but it can’t be classed as open as there is no licensing and not shared in a repository.

This therefore contradicts your point that

I think we definitely agree about the problems associated with OER going mainstream, Peter. The primary misalignment, I think, is simply in definition. I am working with a broader definition of OER that includes content that could be OER but either had not been licensed yet (but is free and open) or is currently not in a repository to share. That would explain, in part, my emphasis (in solution form) on aggregating, licensing etc. as opposed to creating OER. Faculty and instructors in the US create an inordinate amount of content that is actually eligible for OER, and there is support for creating and sharing content. The problem is its lack or organization and management.

I see. It is how we define the terms I guess.

I have started to think about the movement a little more critically recently. So by looking at definitions of ‘openness’, I personally wouldn’t class the informal, not licensed, not shared content, as being an OER.

I wonder if there is enough formal sharing occurring to satisfy funders – when they look back and ask, ‘what did we get for £Xm?’, will they be happy? Not only is there enough content that is easily findable and reusable, but has academic practice been influenced in any significant way across the board.

Interesting discussions – thanks for this contribution.

All good questions, Peter. I would enjoy continuing this dialog, via e-mail etc. if you’re interested. It would be interesting to share research and views in more detail. You can reach me at robreynolds at gmail.