While we have occasionally written about college costs and budgets here at e-Literate, it mostly hasn’t been part of our brief as a site that focuses on technology-mediated education. That is changing, in large part because cost and budgets are increasingly becoming the drivers for change, in California and elsewhere. But I’ve been astonished at how little information seems to be readily available and how little analysis is out in the academic press about even the basics of college and university finances work.

For example, let’s talk about how enrolments impact college budgets. Phil wrote a good post and follow-up post about a month ago about the recession-driven bump in college enrolments. His graph tells an interesting story:

Phil was pointing out the very large divergence between enrollment growth and employment growth. Specifically, the gap is four times the size of the gaps in previous recessions. This suggests that recent and graduates and soon-to-be graduates may struggle to find work. This is a thought-provoking piece of analysis which prompted me to do a little research of my own. But the deeper I dug, the more questions I had.

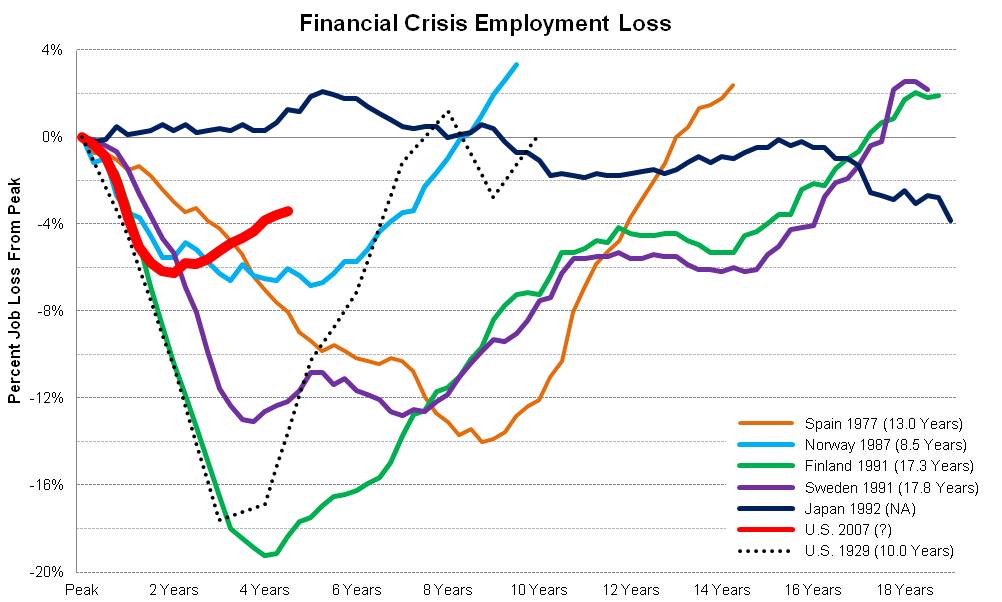

Let’s start with the title of Phil’s post: “This time it’s different.” How different is it? If you look at the recession data from the United States since the Great Depression, the character of the recession looks pretty different. Here’s a graph from the economics blog Calculated Risk:

Obviously, this doesn’t have any enrollment data. But the magnitude of the recession is certainly different. It’s more than twice as deep as the second-deepest recession in the time frame of Phil’s graph. But it’s also much longer. What’s the causal relationship (if any) between recessions and enrollment growth? So far, I haven’t been able to find any analysis of this question. Is there reason to believe that a deeper, longer recession of the kind we just went through could be the primary driver of the enrollment spike we’re seeing now? And if so, what characteristics of the recession are most germane? If you look closely at Phil’s chart, the current divergence really started during the 2001 recession and grew during the 2007 recession. The 2001 recession wasn’t as deep as some of the other recessions on that chart, but it was the second-longest in terms of recovery of the job market (as shown in the Calculated Risk chart). Then again, we don’t see any such correlation after the 1981 recession, which was almost as long as the 2001 recession in terms of job recovery.

Anecdotally, I can tell you that, as the post-2007 job losses ground onward, the community college where my wife worked saw an increase in enrolments of people who lost their jobs and went back to school because they didn’t have any significant hope of getting another job with their qualifications any time soon. But, looking at both graphs here, it seems possible that the character of this recession is anomalous enough that we may not be able to learn much from past patterns. This time really could be different.

Then again, maybe not. If you look at this chart of international recessions from the Oregon Office of Economic Analysis blog, it tells a different story:

From a global perspective, there have been five recessions that were worse than the 2007 United States recession in the past 25 years (from the perspective of depth of impact on the job market and length of job market recovery time). So what do we know about the impact of these recessions on college enrollment? I haven’t been able to find anything so far.

And, of course, it would be simplistic to assume that any relationship between a recession or a dip in the employment numbers and enrollment numbers (assuming there is one) is straightforward. For example, do we see some recessions in which it is more evident that unskilled or semi-skilled jobs are going away permanently than in others? If you’re a factory worker and the last factory within community distance just closed, you might think more seriously about going back to school than if three factories in your area each cut their workforce in half but stayed open, even though latter case would show up on the graphs as a larger net job loss than the former case. What do we know about long-term job shifts as a result of the last two recessions and their impact on enrolments? I haven’t been able to find anything in the reports I’ve read so far.

And what impact does a change in enrollment have on college budgets, anyway? For state schools, it’s complicated. The schools themselves obviously gain tuition for every new student. But in a state system, every student is subsidized. So each new in-state student actually costs the state. That’s why state university systems are often interested in decreasing time to graduation and in reaching students who pay out-of-state tuition through distance learning programs.

Admittedly, I am new to this topic and not an academic, so it would not surprise me if there are studies that answer at least some of these questions. My point is that this kind of analysis is nowhere to be found in the current debates about policy. What has been the impact of the enrollment surge on the budgets of the California systems of higher education, and how long can we expect that surge to last? According to a recent study by the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, college enrollment in California is expected to drop significantly by 2019. How should this projection impact the goals for the current drive toward online learning? According to the same study, there will also be a significant increase in the percentage of non-white college students in California in the same period. It seems plausible that this shift could correlate with a socio-economic and educational preparedness shift, just based on what we know about the distribution of non-white Californians in areas that are poorly served by their K12 education systems. Will remediation be a bigger cost challenge for the state in the coming years than it is this year? If so, shouldn’t California be “skating to where the puck is going to be”?

We need some serious data journalism in the area of the economics of education right now.

This sounds very interesting to me. What sounds even more interesting, however, is the idea that a changing career may be helpful during the time of recession… Or is that deeply affected by the money poured into the financial aid, a billion dollar industry?? The bottom line: Is this because people ‘need’ better education or because banks need more borrowers to circulate their money? Just a thought.

It’s hard to make a blanket generalization, but I’m pretty confident that the students coming into my wife’s community college were not there because some loan officer persuaded them that it was a good idea. I think people are probably pretty good at knowing when they are in dead-end careers. What’s harder, I think, is making a smart calculation about which degree to get at which school and how much it is worth paying. That’s where I think marketing comes in, more from the schools than from the banks.

Great article… I am not an education expert, but do understand technology and its impact. Could you conclude that the innovation from e-learning and its maturity is a key reason for these economic trends?

Not at all, Tom. I’m mainly looking at the effect of economic trends (specifically employment in times of recession) on enrolment. And there’s not really enough data to conclude much of anything here, other than the fact that we need more data.