The product I am going to tell you about here was created by two of my former seventh and eighth grade students. I love these guys. So yes, I am biased. But that knowledge also presents an opportunity. I am 100% confident that they have only the best of intentions. With that in mind, I can look at the genesis of an idea for pre-K ed tech—a particularly fraught corner of a fraught field—knowing that there is no scam or hidden agenda here and see some of the challenges that arise when trying to go from best of intentions to implemented product.

I think Starling is a great idea that has the potential to do a lot of good in the world. But I also think it will raise some eyebrows.

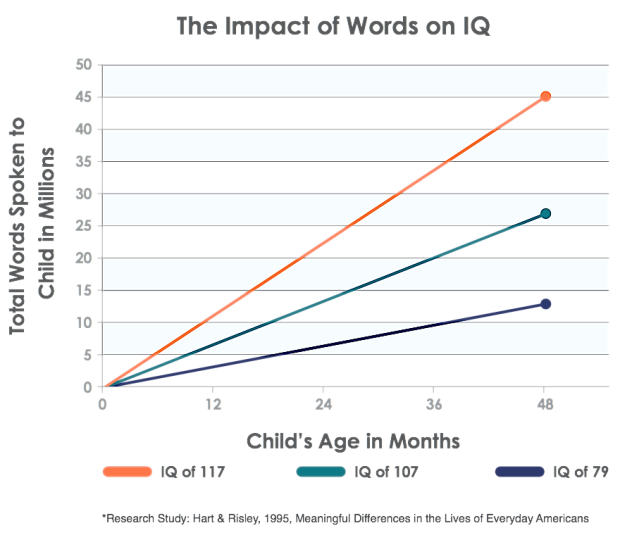

The Boggiano brothers started their current journey when they learned that the number of words that children hear spoken to them in the first four years of their lives has an enormous cognitive, emotional, and social impact for the rest of their lives. If a child isn’t getting the right kinds of social interaction as an infant and toddler, then intervention in kindergarten may already be too late in some respects.

There is a strong socioeconomic element to this effect. Parents who have to work multiple jobs are going to have fewer opportunities to engage with their children. Parents who are not literate, or who were not read to as children, are going to be less likely to read to their children. And so on. This “word gap” perpetuates and reinforces socioeconomic gaps across generations. Furthermore, as even middle class parents are working longer hours, spending more time on smart phones, and so on, it seems like the word gap could be a potential problem for just about any parent.

So the brothers got an idea: Why not build a kind of Fitbit for infant language exposure? Why not create a device that helps parents keep track of how much they are talking to their children, set goals, and see and improve their progress toward their goals? They got some guidance from Stanford’s Language Learning Lab at Stanford’s Center for Infant Studies and, along with co-founder Nicki Boyd, set out to design the product. Long story short, they have built prototypes, piloted them, and now are seeking funding to scale up production via Indiegogo.

I’ll set aside the technical complexities of designing such a product for now, but there are some business and implementation complexities worth exploring. First, in order to change the world, they first have to stay in business. Who is likely to buy the product first? Not the families who have the biggest word gaps. It’s much more likely to be the families that are already giving their children every advantage possible. So that’s who they are marketing to as their first customers. There’s a Tesla-like business strategy here, not in terms of price point but in terms of trying to create a market by targeting the demographic with the most disposable income and the ability to be trend setters and taste makers. But there is a danger here that Tesla doesn’t have, particularly when you add the product’s data collection capabilities into the mix. Starling could be easily be pigeon-holed—pardon the bird pun—as a product that rich parents whose main concern is whether they will be able to get their child into that exclusive kindergarten program buy to make sure that their nannies are speaking the correct number of words to the children. This is not a product design problem. It’s not even primarily a marketing problem. It’s just one of the complexities that arises when product meets world.

On the social mission end of things, simply providing economically challenged families with a gadget, however well designed it may be, is not going to magically transform families. Starling’s creators are well aware of that problem. That is why they are working with an existing non-profit called Literacy Lab that works directly with underprivileged families and is focused on the word gap and early childhood language learning problems. The idea is that Starling will be a tool that parents and their support organization can use together as part of a more holistic approach. Their Indiegogo page gives you an option to donate a Starling to a family in need being served by Literacy Lab. That’s the option I chose. But I suspect that the niche where Starling has the most potential for social impact is working class families that are economically (relatively) stable but where the parents have limited literacy, or no family history of college education, or no experience being read to, or came from a family where their own parents were working multiple jobs a week. Those are the families that can probably get the most benefit with the least amount of extra help.

The other complexity worth mentioning here is privacy. Starling doesn’t record conversations, and it’s hard for me to imagine what advertisers could do with information about how many words you spoke to your one-year-old even if the company chose to sell that information. But it’s hard not to feel at least a little uneasy about the idea of recording your interactions with your child pretty much from birth and putting that information “in the cloud.” I actually don’t know the degree to which the product uploads info to the internet at the moment. It appears that the device stores the information locally until you access it with your smart phone, which wouldn’t necessarily require any of the data to go outside of your local area network at all. But, for example, if the product is going to be used as a communication tool between parents and support folks like those at Literacy Lab, that starts pushing product development in the direction of online dashboards.

I believe in what the founders are trying to accomplish with Starling and I trust them. I have contributed to their project and I hope that you will too. But Starling is also an excellent case study in just how complicated ed tech can be, even when you come to it with a good idea and the best of intentions.