I have volunteered to give my local community college some advice regarding some LMS migration decisions they have to make—if to migrate, when to migrate, how to migrate, and so on. In many ways, they’re a pretty typical school with some pretty typical problems, so I thought it might be worthwhile to write down some of this advice for others in similar situations. You might be one of those others if at least three of the following are true:

- You work at a small school of 3,500 students or less.

- You have a couple of dozen faculty “heroes” who are using the LMS heavily, a bunch more who just stick their syllabus in it, and a substantial number who don’t use it at all.

- You offer a small number of distance learning and/or blended courses, but you don’t have any online degree programs or similar systematic collections of online classes.

- Your school hasn’t migrated to a different LMS in a long, long time. Maybe ever.

- Your LMS is hosted because you don’t have the IT staff to manage it internally.

- Your “integration” between your Student Information System (SIS) and your LMS is to manually export CSV files from the SIS and upload them into the LMS.

- You have been on Blackboard CE since it was WebCT CE version 4 or earlier.

- You’re not sure if you can handle a migration to anything from either a staffing or a budgetary perspective.

- Don’t panic: Lots of schools in your position have managed to migrate to a new LMS. It isn’t easy, and it isn’t fun, but it is very much possible, even within the resource constraints that you probably have. Keep reminding yourself that migrations happen all the time.

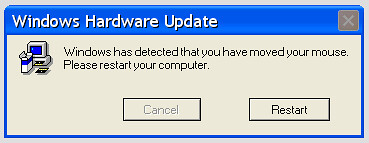

- Migration is inevitable: Computer systems change. Even if you have good reasons to hold off moving for as long as you can, sooner or later you are going to have to make the leap, say, from Windows 95 to Windows XP (or to a Mac). If you are a Blackboard CE customer, this is a particularly apt analogy since CE8 is essentially the last release of CE as we know it. After that, you will be migrating either to Blackboard proper or to something else. I am sure that Blackboard will do everything they can to make the migration from one of their products to another as easy as possible, just as Microsoft made moving from Windows 95 to Windows XP or from XP to Vista as easy as they could. But the fact of the matter is that just adding new features and improving the user interface almost automatically mean that existing faculty will need to be retrained and that some courses will need to be redesigned. There’s no avoiding it.

- Migration can be an opportunity: Chances are good that you’d like to do more with your LMS than you are able to do right now. If you can make a choice that, over the long run, reduces the amount of help desk support you have to provide, reduces the effort that new faculty have to make to learn the system, and/or reduces your ongoing costs, then migrating will free up more resources to accomplish more of what you want.

- All of these systems are pretty good: It’s easy to get worried about making a “wrong” decision and picking the “inferior” product. The truth of the matter is that, given the needs of your institution (both present and foreseeable future), any of the major systems available in the US that I have some familiarity with (ANGEL, Blackboard, Desire2Learn, Moodle, and Sakai) will provide you with adequate functionality. That doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t look at differences in capabilities, but it does mean that you shouldn’t let yourself get obsessed with them. In particular, if you are currently on Blackboard CE, any of these systems will be as good or better in terms of functionality and all will be improvements in terms of usability and stability. CE is a relic of a previous generation of technology that is long past its natural life, which is one of the reasons why even Blackboard wants to get you off of it as soon as they can.

- Accept the possibility that you may have Stockholm Syndrome: Regardless of which LMS your school is on, you may have just read that last bullet point and thought, “Well, our system is doing just great. It was only down 9 days last semester—a big improvement from the 3 weeks of down-time the previous semester. Granted, most of that was the entire first week of the semester, but still.” If so, then you, my friend, have Stockholm Syndrome. It is natural for people to try to make the best of a bad situation, especially when they are the ones who often get blamed for it (fairly or not). If you are an LMS support person, then it is likely that you are too close to the day-to-day operations to have good perspective on all aspects of how well your current system is meeting your school’s needs. Make sure you get input from people with a broad range of experiences, roles, and perspectives.

- All of these systems are pretty bad: Relative to Blackboard CE, and relative to the baseline needs you are meeting now and hope to meet soon, all of these systems will probably fare pretty well. But part of that is because our expectations are low. The state of the art in LMS design is frankly not great. If you find things that you hate about LMS A but absolutely love everything about LMS B, then you probably haven’t looked hard enough or long enough at LMS B. Try to keep that in mind if you find one LMS in your process getting heaped with praise and another getting ridiculed.

- Usability matters: You’d probably like to see more faculty and students use your LMS in richer ways than they are now but are struggling to keep up with your current support load as it is. Therefore, you need a system that is easier for people to figure out how to use without your help. Having a system with 39,000 seldom-used features that require a course to learn how to use is not as valuable to you as having a system with 39 features that most people will find useful and can figure out how to use on their own.

- You may not be a good judge of usability: In most cases, a system seems easy to use once you know how to use it. Therefore, a system with which you are intimately familiar will probably look easier to use than one with which you are unfamiliar. That is not a good test of usability.

- Your current faculty LMS heroes may be the worst judges of usability: There is nobody on your campus more likely to have Stockholm Syndrome than the faculty member who taught her first online class using your current LMS, has never used anything different, and has devoted literally hundreds of hours to optimising her course—squeezing every ounce of value out your current system by exploiting every weird little feature and even figuring out how to turn a couple of a couple of bugs to her advantage. There are ways in which her perspective will be extremely valuable to you (which I’ll get to shortly), but judging usability is not one of them.

- Somebody who has taught using multiple LMS’s could be a good judge of usability: Faculty members who have taught using 2 or 3 (or more) LMS’s generally have some sense of what differences between platforms really matter and what differences don’t in a practical sense. If you have such faculty members on your campus, then you really need their input.

- Somebody who has never taught in any LMS but would be open to doing so in the future could be a good judge of usability: You don’t want somebody who still can’t do an email attachment, but you do want somebody who is not a technology fetishist and has no preconceptions. Talk through with this person a small handful of tasks or activities that she might want to try in her first or second attempt to web-enhance her class. Then ask her to look at the candidate platforms just from the persective of learning how to do those particular tasks. You’ll learn a lot about how easy each platform will make it to grow your faculty commitment.

- Find friends at peer institutions that use the platforms (and support vendors) you are considering: You want people who will be honest with you about the ups and downs, and you also want people who are going to be reasonably generous with their time. They should be happy enough with their platform and vendor choices to be advocates, but not so happy (or so cozy with the vendor) that they won’t tell you what sucks about it. (See “all of these systems are pretty bad” above.) The vendors can help you find contacts if you can’t find them on your own, but you’re better off finding them on your own if you can.

- Get your LMS faculty heroes to pair with your friends at peer schools: The best way to use your heroes is to have them sit down with well-informed and passionate teachers who use and advocate for other platforms. These peer-to-peer conversations will help them develop perspective on the guts of the platform alternatives that will be very valuable to you. It may also help them come to terms with the inevitable grieving process they will be going through at the prospect of having to give up the system they have invested so much into mastering. Unfortunately, the migration process is probably harder on your LMS faculty heroes than it is on anyone else, even including the support staff.

- The quality of the support vendor is almost certainly more important than the quality of the software: If you host your system with somebody else, then you are almost completely at their mercy. If it goes down or has weird problems, you can’t do anything about it yourself. You need a vendor you can trust. Ask your peer schools about their support experiences, look at the Terms of Service in the contract carefully, and place a high priority on this portion of your evaluation.

- Ask your prospective vendors for examples of things their companies have done that demonstrate their values: Seriously. Because the support relationship matters even more than the software, your LMS selection process should feel a little bit like a faculty search committee. You need to know if you can count on these people. Ask them a few job interview-type questions.

- Don’t assume that you know what the deal is with open source: There are a lot of myths out there about what it takes to run or support an open source LMS. For our current purposes, I’ll leave aside the lengthy explanation of exactly what those myths are and why they are false. Instead, let’s think about it this way: Your relationship with your LMS is not that different than your relationship with GMail or Yahoo! Mail. It’s hosted on somebody else’s servers; you don’t know anything about the details of the software—the programming langauge it’s written in, how much of it is open source, what the architecture is, what hardware it runs on, etc.—and you don’t care. (In fact, both Google and Yahoo! are heavy users of open source on their servers, which means that you use open source all the time and you don’t even know it.) What matters to you is that the thing that appears in your web browser works reliably and does what you need it to do. Go to the open source LMS support vendors. Tell them what your requirements and capabilities are. Either they will be able to meet your needs or they won’t. Don’t decide in advance of getting the facts.

- Ask both your peer institutions and your prospective support vendors for their migration experiences: The migration is the single hardest part of this. But remember, others in your position have done it. Find out how. Get lots of advice and lots of war stories. Listen carefully to your vendors when they talk about migration. Ignore what they say about how easy it will be. Most salespeople (even many of the good ones) will not give you helpful (or even entirely reliable) answers about this part. Instead, what you want to pay attention to is how detailed their process is. Have they accounted for all the bits that your peer institutions say are hard? Do they sound like they know what they are doing? Will they give you the support you need?

- Don’t worry too much about the long-term financial viability of the vendors: On the one hand, none of these vendors is large enough that going with them will assure you that they won’t be acquired or go out of business. Blackboard is substantially bigger than its competitors, but it’s not even close to being big enough to be immune from the vagaries of the markets. On the other hand, none of these vendors are likely to fall off a cliff very soon either. You know from experience that the prospect of migrating to another LMS is scary, and you avoid it as much as you can, even if you’re not happy with your current situation. To varying degrees, the LMS vendors all have captive audiences. While they may not grow, they are more resistant to economic downturns and other sudden changes of fortunes than many other industries. The open source support vendors are generally the smallest and therefore the most vulnerable but, on the other hand, with open source your platform choice is decoupled from your support vendor choice. If ANGEL goes out of business (to choose a random example of one of the proprietaries), you can’t go anywhere else to get support for the ANGEL platform. If your Moodle support vendor goes out of business, you can take the same Moodle open source LMS and get support from a variety of other vendors without having to migrate. So, in general, while I’m not saying you should ignore the viability issue completely, I wouldn’t put too much weight on it.

- Consider long-run costs as well as short-run costs: Both in terms of whether to migrate in general and what to migrate to in particular, you will face questions about trade-offs in short-run versus long-run costs. In many cases, schools will look at short-run costs and ignore long-run costs. Don’t do that. If it costs you more in Year 1 to migrate to LMS A, but the total cost (due to lower license fees, service fees, staff support demands, etc.) turns out to be lower by the time you get to Year 3, don’t you want to know that? Migration may be cheaper than staying put, and the more expensive migration in the short run may be cheaper in the long run.

…and the one that is missed because of the begged question – “Consider that you may not need an LMS AT ALL!” (especially given the incredibly limited usage scenario you outlined.) Remember “LMS are an answer to a question begged by an outdated business/educational model” 😉

I frankly don’t think that’s a good question for this audience in this situation, Scott. To begin with, we’re talking about resource-strapped colleges that are struggling to meet their core needs. When you talk about “an outdated business/educational model”, you’re talking about a huge rethink of fundamentals that they can’t take on in the context of a relatively tactical decision like this one. There are major policy and training (not to mention legal) issues involved with just moving from an LMS to a more Web 2.0-like approach even if you *don’t* presuppose the fundamental changes you imply in the structure of the institution itself. (And by the way, a couple of dozen faculty using the system heavily is not what I would call “incredibly limited usage” for an institution in the 1,500- to 3,500-student range.)

It’s all well and good to advocate for a return to first principles, but I think you have to own up to just how much is entailed by what you are advocating.

This is a great article. I am on the board of a small independent school and will use this information for the administration. Thanks for taking the time to put it together.

Glad to hear that it’s useful, John.

Hey- this is nice. I’d love you know what you think about free LMS tools that are out there. Did you know that you can migrate from a Moodle to something like http://www.edu20.org which is not hosted?

What do you think about that?

Drezac

First of all, just because you don’t pay for it doesn’t mean it isn’t hosted. “Hosted” just means that it runs on somebody else’s server rather than your own.

There are a number of outfits that are trying to find alternative revenue models for their online learning environments right now. Some of them are interesting and worthwhile experiments, but I’m not at the point yet where I’ve seen one that I would be comfortable recommending to schools in the situation I’ve described here.

I think this is a very exhaustive list of criteria to consider for ANY education institution nowadays… Even big ones are considering outsourcing because of lack of internal resources anyway. Amazing how a budget crisis puts everything back into perspective.

It seems like you have spent some considerable time gathering these thoughts, and this post is definitely going to be useful for a lot of people. Keep it up!

Great article, Michael – very useful. What really struck me was the one about “Your current faculty LMS heroes may be the worst judges of usability” – I definitely found in a move from WebCT to Moodle that the hard core WebCT users who were there from the very beginning were:

*the most vocal

*the most aggravated by any perceived issues or lack of functionality

*most likely to email administrative higher ups and claim we got a bad deal

*some of them were the most resistant to actually migrating, waiting until the last minute to migrate and to take training (if at all)

*frequently quite wrong about the actual functionality, simply due to not knowing the new system

*eventually came on board, using and liking the new functionality that opened up to them

Interestingly, an LMS migration really does stir things up – the old LMS heroes seem to have taken on a new role as regular LMS users. Actually, from the perspective of helpdesk support staff conducting training, etc. the interesting thing is to see how other users have stepped up as the new LMS heroes – doing things in new ways, exploring new tools previously unavailable, coming up with new and interesting course designs, etc. And the cycle continues….

Thanks, Clark, that’s great feedback.

A nicely balanced posting Michael. I’ll keep this one in my back pocket just in case

in proves to be useful in my new day job.

I’ll add one more thought, which I think was implicit in your comment about all the major LMSes are ok. The LMS has become a commodity. By that I mean, the features are all pretty well understood and there’s not anything lacking. I could say the same thing about word processors (I’ll take Word from about 15 years ago)

or relational databases (SQL stopped changing 20 years ago). Once a software market reaches that point, it’s not about adding more features, it’s about who can

execute the best, aka service, technical support, bug fixes and so on. I’d still suggest that looking at features, and very much at usability, is a big deal, but that

you are likely to find more differentiation in your decision making on the support, execution, and of course cost.

Glad to see you are still bloggin’ away Michael!

Thanks, Dirk. I hope your new day job is going very well. We miss your great input on our product development.

I agree with the core sentiment of your comment, although I’m not sure if I would call it commodification. Commodification usually happens with a mature product, and I would say that the LMS is more in a state of arrested development. You will see a slow accretion of coarse-grained features (e.g., ePortfolios) continue, and you’ll continue to see a lot of fiddling and differentiation in the long tail (an area that is mostly off the critical path for the kinds of schools I’m targeting in this post). But for the most part, until there’s a real rethink of the product category as a whole, I think you’re right.

Great article, Michael – we appreciate your help!

Great article. I am really glad I found your blog. I run a very small language school and am actively looking for a LMS. I might go crazy before I decide on one. Do you have any suggestions for a small business with about 100 students? I have found a number of tutoring management systems but they only offer the administrative side of the business (scheduling, time-sheets, reports). I would like a system that also offers the content part of the business (online courses, quizzes, course catalog). Any help is much appreciated.