I’m thrilled to announce that my long-time friend, colleague, and sometime mentor Curtiss Barnes is joining e-Literate and the Empirical Educator Project. We’re in a transitional phase right now, but the goal is for him to become a full partner in the business. For those of you who really know Curtiss, I don’t need to tell you why I’m so excited about this. But for those of you who don’t know him, or who only know him as that textbook publisher executive guy—seven years at Pearson and three at Cengage—an introduction is in order. I was planning on making this post brief. But has Curtiss and I chatted about his journey in education, I realized that his story contains interesting lessons about both the history of EdTech, the challenges of making it work for academia, the future of academic work, and also the future of e-Literate.

Also, Curtiss has influenced me and embodies the core values and mission of e-Literate in some non-obvious ways. I don’t feel that rattling off the typical marketing blah-blah-blah about so-and-so joining the company would really get at why his decision to work here is meaningful to me and why I hope it will turn out to be meaningful to you. So I’m going to use this opportunity to tell a broader (and longer) story.

A familiar origin story

Curtiss was, in his words, a “military brat.” His father was an enlisted service member in the U.S. Air Force who was trained as a linguist. While it’s not quite accurate to say that Curtiss was a first-generation college student, neither of his parents and most of the adult relatives he knew growing up had college educations. But as we know, lack of education and lack of intellectual curiosity or capability are not the same thing. His father learned to speak several languages—Vietnamese during the Vietnam War and then Russian during the Cold War—as part of his work in the Air Force. Curtiss spent most of his childhood in West Berlin, Germany at the International school, where he became interested in the differences between the German and American educational systems.

He went to Clark University for his undergraduate degree, in part because Clark gave him a good scholarship that made the price attractive relative to some state universities he was considering. That interested him too. How did this whole college finance thing work in America? He wrote his undergraduate thesis in Economics on philanthropy. (He also met his wife there.)

And for a while, Curtiss’s professional path was one that will be familiar to many academic administrators. He got a job working in Clark’s advancement department (i.e., fundraising) immediately after college. From there, he moved to the University of Pennsylvania. At first, he was involved in fundraising again. But that got him working closely with admissions, alumni relations, and institutional research. For family reasons, he managed to convince Penn to let him move out to the West Coast, where Wharton in particular had an interest in cultivating a stronger presence. While there, he eventually got involved with the creation of a sustained West Coast operation including Wharton’s West Coast Executive Education and Executive MBA programs.

So far, this may sound familiar to some of you (although the people who tend to follow this specific path often end up in different parts of the academic institution than the historic e-Literate readership). Most people who end up in academia are there because they are intensely curious about something. Often it’s an academic subject, but sometimes it’s some aspect of how the university works, like pedagogy or sustainability or policy. If your early stops on this train are a set of jobs working in a university as an undergraduate, there’s a good chance that you eventually end up going to graduate school. Which is what Curtiss did. He went to Wharton for his MBA.

And then his career took an interesting turn.

Product management

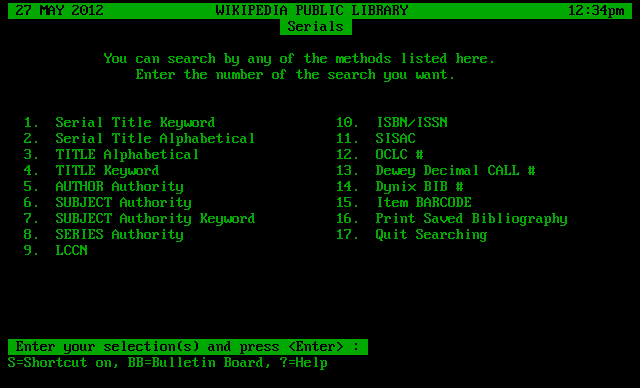

While he was working on his MBA, he took some time off to work at a startup called Campus Pipeline, which wasn’t a very successful company but turned out to be a fantastic place to work if you were curious about how technology would begin to impact higher education over the course of the next decade. This was back in 1999, when a lot was happening. Peoplesoft had created what became Campus Solutions from a system built by a team at UCLA. In the early days, it was a green screen application. For you young ‘uns in the audience, this green screen isn’t the feature in Zoom that lets you look like you’re web conferencing from the beach. It means that the user interface of your software typically looked something like this:

It was literally a screen that was all green, all text, and no mouse or pointer functionality. Peoplesoft and its competitors were very focused on getting the transactional registration and accounting details right so that people were registered for the right classes, got credit for them, got billed for them, and so on. And on making the interface less awful for the administrators who had to use the system. They weren’t terribly focused on the stakeholders beyond the back office folks like the registrar. People of a certain age will remember that students used to register for courses by standing in lines in the college gym and filling out paper forms. That was one problem to be solved, but the companies that made these Student Information Systems (SISs) were not really ready to take it on yet. They were busy working out the kinks in the core software.

Correction: While many of these early SISs had green screen implementations, Peoplesoft did not.

Another change of the time was the rise of the LMS. This was right at the time when LMSs were beginning to achieve widespread adoption. But they were pretty simple applications back then. They didn’t integrate well with these new SISs, and they hadn’t yet evolved good software for sharing information beyond the needs of individual classes.

And then there was this thing called the World-Wide Web. The internet search giant that was taking over the world—I’m talking about Yahoo!—was changing the way everybody was thinking about information. This word “portal” was making its way into the popular lexicon, even if not everybody knew exactly what it meant.

Campus Pipeline stood astride all of these trends. Or tried to. There were obviously some big new ways in which technology could help education, but it wasn’t yet obvious how they all would fit together usefully. The company never quite found its footing, in part because it was just too early to the party. It pivoted so often that perhaps “pirouette” would be a better term. Campus Pipeline survived the dotcom implosion in 2000 and was eventually managed to get acquired by the company that, several mergers later, would become part of Ellucian.

But the important aspect for our story is that Curtiss got bitten by the product management bug. He understood some of the challenges and changes facing higher education from his experiences on the inside. Now he had a chance to see what it was like to design products that helped with these problems. What if students didn’t have to line up in the gym to register for classes, as they had from time immemorial? What if they didn’t have to work their way through a maze of campus departments to get basic information and could instead just look it up on the web? How could students be served better and institutions work more effectively if these new, expensive software products that the universities were buying could actually integrate with each other in some way?

It’s intoxicating. I have teased Curtiss that there is a certain Forrest Gump aspect to his story of always stumbling into the right place at the right time, but the truth is that a lot of this was about him following his curiosity. This is partly a story of what it can look like when we stop defining ourselves by what we have done in the past and start imagining ourselves based on what we could do in the future—as individuals, organizations, and a sector writ large.

Products serving people

Curtiss followed Campus Pipeline into the bowels of the SIS world and soon found himself at Oracle. This was soon after Oracle had acquired Peoplesoft in a publicly acrimonious hostile takeover. And it wasn’t like Oracle otherwise had a sterling reputation before this. They were generally reviled as a company, even if their database product was highly regarded. Further, SISs were still relatively primitive but already very complicated. They are extremely hard products to build well because so little about the ways in which they were used was standard. Again, this is not exactly the description of an easy and fun job, but it was a great place to learn. (There is a pattern in Curtiss’ life choices that is developing at this point in our story.)

Higher education is not known for its loving embrace of aggressive corporate empires. Needless to say, the acquisition was not welcome news for many Peoplesoft Campus Solutions customers. To say the least. Luckily, Oracle was smart enough to keep most of the really wonderful group of people in the Peoplesoft higher education team (including some who had come from the UCLA team that developed the original software on top of generic Peoplesoft). Curtiss started at Oracle with the word “strategy” in his title. Strategist is often a difficult role to have because at many companies, everyone thinks they’re a strategist and almost nobody is really any good at it. At Oracle, being a strategist meant that Curtiss and his fellow colleagues were the connective tissue—and sometimes the mediators—between the sales team, the product team, and the customers. Their job was to understand how both salespeople and product people listen to customers (and each other) and synthesize what they heard into, for lack of a better term, a strategy. He also represented Oracle on the IMS Board of Directors (while I was contemporaneously serving my tour of duty representing Oracle on an IMS standards development committee).

At that time, Oracle had a couple of challenges that Curtiss worked on with his (truly excellent and often unsung) colleagues in Oracle’s higher education group at that time. First, they had to prove to the Campus Solutions customers that their voices would be heard and their needs met under the new ownership. This they did, at least to the degree that anyone can make people feel warm and fuzzy about an inherently crazy-making product category. (The number of people who have ever in human history said “I love my Student Information System so much!” is approximately zero. Almost as many as have said the same thing about their LMS grade book.) They really did win a lot of trust back, which is something you can only do by consistently listening to clients, making sure you are understanding their needs, and responding to them as quickly, empathetically, and effectively as possible over a long period of time. When Curtiss and I talked about what he considered to be the highlights of his time at Oracle, this work was the first thing he mentioned (along with his colleagues).

The best reason to make a living working on products is that you love solving other people’s problems. This means that you have to learn to love—or at least empathize with—the people whose problems you are solving.

The second challenge that Curtiss and his colleagues tackled was taking Campus Solutions to international markets. The good news (from a business perspective) was that large parts of the world were lagging the US in the adoption of this sort of product, so there was an early opportunity to get into those countries and serve those schools. The bad news was that universities function very differently in different countries. So there was a ton of product localization work to be done. Tech people tend to throw that word around as if it means “translate the labels into another language,” but really it means understanding how customers in a new area have different needs—typically influenced by different cultures, sustainability models, and regulatory requirements—and then redesigning your application to serve those needs (without breaking it for existing customers). This is really hard, especially for an application that gets deep into the quirkier and more arbitrary—and yet critical—aspects about how different universities and education systems work, like how credit is awarded and who pays how much for what aspects of the education at what times. So for a person with the word “strategy” (or “product”) in their title, growing into international markets should mean learning to empathize with different kinds of customers well enough to understand and help to address their needs and wants.

The third challenge that Curtiss and the team wanted to take on was to better serve their customers’ core mission of teaching and learning. This is why I was recruited to Oracle. I was their first hire who was supposed to be an expert on the “education” part of higher education. Like Curtiss, I had started off working in an educational institution and got bitten by the product bug. I had done some consulting work that had periodically gotten me into product design, but Oracle was my first gig where product design was my full-time job. I had an unusually large number of colleagues that I liked, admired, learned from, and still consider friends to this day. Curtiss is one of them, but he also was a mentor for me in a way that has had a profound impact on e-Literate.

Big companies like Oracle are weird in their own special way. If you’re an academic, you have probably had your moments when you’ve clenched your fists or pulled your own hair out in frustration that what should be a simple, rational process to accomplish something that obviously needs to be done is absurdly hard or even impossible. Corporations are no different in that regard. Their dysfunctions are often completely different—to the point of sometimes seeming incomprehensible to academics—but the end result feels striking similar from the inside. Understanding why organizations are dysfunctional in their own particular ways can be hugely helpful for both effectiveness and mental health. It helps you get more done while saving yourself some stress by avoiding battles that you can learn to recognize as unwinnable earlier on. Both of these are critical. We all want to spend as much of our time being effective at work and as little time as possible spinning our wheels. Curtiss had been a student of this dysfunction starting long before I had. He understood corporate dysfunction, academic dysfunction, and the codependencies between the two kinds of organizations. He taught me ways of thinking about these problems that animate some of my best writing and work in the sector to this day.

Ultimately, the team was not successful in getting Oracle to make a major investment in the teaching and learning side of education. It felt like we got close a few times, getting multiple meetings with top executives who seemed receptive. For me, the final nail in the coffin was Oracle’s acquisition of Sun Microsystems. It became clear that, while the company was happy to have the higher education business, they were hunting for bigger game. We were not going to be a priority. This was the bleeding edge for a company like Oracle at that time—along with moving to the cloud—but the company wasn’t ready to bleed for education. It was time to either come to terms with that fact or move on.

Products supporting teaching and learning

Curtiss left for a job at Cengage Learning, where he could get closer to the education problem. I quickly let him know that I wanted to follow him both because I wanted to continue to work with him and because Cengage seemed like an interesting opportunity to attack a meaty problem.

I’ll speak for myself here: I thought I was going to Cengage to start a methadone clinic for one of the major textbook publishers. The industry was addicted to high prices and frequent republishing of new additions to tamp down the used book market. As is often the case with addicts, it took a long time for the industry to admit that it had a problem. Curtiss was the right person to help them with this problem, and he was being hired at a high enough level that I had hopes he could help them do it (although he did have that pesky word “strategy” in his title). He also persuasively argued that the right team was in place to make the change. Cengage had hired Chris Vento, who was famous in EdTech circles for leading the creation of WebCT Vista, which was a cutting edge LMS in many ways in its day, and for driving some important standards work at IMS. Chris was the visionary behind their new digital courseware platform—though that term wasn’t in common parlance yet—called MindTap. Once I saw what he was working on, I was sold. Chris is one of the most brilliant EdTech product visionaries I’ve ever met. It would be a privilege to learn from him.

I wanted to work with Curtiss, Chris, and other valued colleagues to help Cengage re-invent curricular materials products as something new and genuinely educationally useful while pushing the company toward a healthier business model in the process. This was a growing passion of mine—to make EdTech healthier and more responsive. Continuing to learn about how to do it by working with and learning from Curtiss felt right.

It was a good hill to die on.

While the first generation of MindTap was fairly successful, we ultimately failed to achieve our larger ambition—at least in the time frame that the three of us stuck around the company—in part because the patient hadn’t reached the first step in the 12-step program. It would take a number of more years for the publishers to come around to our way of seeing things, and it’s arguable whether they’ve come far enough or moved fast enough.

During my personal trough of disillusionment with Cengage, Phil Hill approached me about starting a consulting business together. It seemed like an idiotic idea, which was one of the reasons that it appealed to me. If I was going to fail to make a difference, I wanted to at least do it my way.

But Curtiss stuck to his guns. He moved on to Pearson, where he finally shook the “strategy” label and found a place where he could help shepherd truly large-scale change.

Bringing the “Ed” and the “Tech” together

I was worried about Curtiss at first, for two reasons. First, my opinion of the industry as a whole was at an all-time low. And y’all know where my baseline is. Second, Pearson had a reputation at the time of being an old boys’ club and a highly political place, which is the antithesis of how I think of Curtiss.

But he steadily climbed the ladder there while still staying recognizably Curtiss. Before I knew it, he was essentially overseeing Pearson’s entire digital product portfolio. Textbook publishers’ organizational charts and accounting systems are even weirder and more Byzantine than many universities, so both describing what it means to “oversee” a portfolio at one of these companies and measuring the size of it in any definitive way are incredibly complex. Depending on how you count it, the products under Curtiss’ purview were worth anywhere between hundreds of millions and well north of a billion dollars in revenue. He certainly didn’t have absolute authority over that portfolio, but he had enormous influence.

Curtiss took some of the ideas that had failed to get traction at Cengage and helped drive them deep into Pearson. Digital curricular materials would be, as he puts it, “more than just a book under glass.” There would be educational affordances designed not just for the convenience of the professor but to support more effective teaching and learning. This meant bringing learning designers and UX designers into the center of the design process. It meant battling the notion that every discipline—which in the world of textbook publisher politics really meant every major editor—was an island unto itself and therefore should have been allowed to build its own half-baked platform. Pearson CEO John Fallon, about whom I have decidedly mixed feelings, deserves immense credit for pushing the company to hold itself accountable for its role in impacting educational outcomes. But it fell to Curtiss’ team, as well as to Kate Edwards and her colleagues in Pearson’s research and efficacy group, to actually operationalize that commitment and make real progress toward it.

One of the aspects of my professional perspective that I’m proud of is my ability to recognize important, hard-won progress without losing sight of how far we still have to go. That’s a trait that I share with Curtiss and may well have learned from him. The publishers are still a mess, and it’s very much an open question regarding where they go from here. That said, the sector has made substantial progress in figuring out what the potential of digital courseware can be. Some of the credit for that undeniably belongs to Pearson, and Curtiss played a significant part in that transformation.

Remember, this is the same guy who started out his professional life as a fund-raiser for his alma mater. In the current environment, many of us are likely to face some strange and unexpected career choices. We are who we choose to be. Or as the great Yogi Berra once said, “When you see a fork in the road, take it.”

Curtiss’s last role at Pearson shows him once again following his nose. He spent some time looking at the problem of life-long learning and career development in the 21st Century. The ongoing educational needs of today’s workers can no longer be met by the traditional corporate training and development department. (More accurately, the need can be met by T&D departments even less effectively than ever.) How can we build stronger, more agile partnerships between higher education, the corporate sector, and non-profit actors to address this challenge? As usual, Curtiss is onto the next frontier.

Run, Forrest! Run!

A really bad career decision?

So now Curtiss is starting to work with me at e-Literate and EEP. A person with his experience has options. I’m humbled—and honestly a little perplexed—that he’s chosen this particular option, but then, he’s never been one to take the easiest or most obvious path.

This post has been an introduction to my friend and colleague, but it’s more than that. And it’s also more than just a parable meant to encourage you about your own future career choices (though it is that too). Times are changing and we must change with them. e-Literate must change too. I’ve been signaling that in some of my recent posts. This is the first concrete sign of those changes. I want to help you make the world a better place, in this moment, in ways that matter. My skills are not equal to my ambition, and anyway, I’ve always enjoyed my job most when I’ve had the privilege of working with people that I admire. Curtiss is one of those people. You’ll be hearing his voice here on e-Literate soon enough. And you’ll hear about new initiatives that we’re cooking up. I can’t wait for you to see what’s coming.

In the meantime, my next post in this series will cover Curtiss’ history with pets, including his formidable chicken coop-building skills.

I kid! I kid!

(Maybe.)

This makes me so happy…

Congrats Curtiss! This is a great move.

Congrats Curtiss!! I wish you the best!

Congratulations Curtiss!

Happy, happy — Joy, joy This is really wonderful news! … gettin’ the band back together

Fabulous read, loved both the history lesson through your (Michael’s) lens, and Curtiss’ back story. I was at Pearson when you all landed at Cengage and I was terrified (competitively, that is). Now, I get to be elated – so looking forward to the next phase of eLiterate and EEP.

Curtiss does deserve much of the credit for whatever progress Pearson has made. He is a true leader and visionary, someone people want to work with and for.