Our favorite technology industry blog—Ben Thompson’s Stratechery—has a great piece up about Amazon’s relationship to open source that also explains a lot about the tectonic shifts in the LMS market. The story he’s interested in telling is about the dynamics behind Amazon’s move to essentially copy and abandon a popular open source database called Mongo DB. His introductory analogy to the music business is revealing and worth quoting at length:

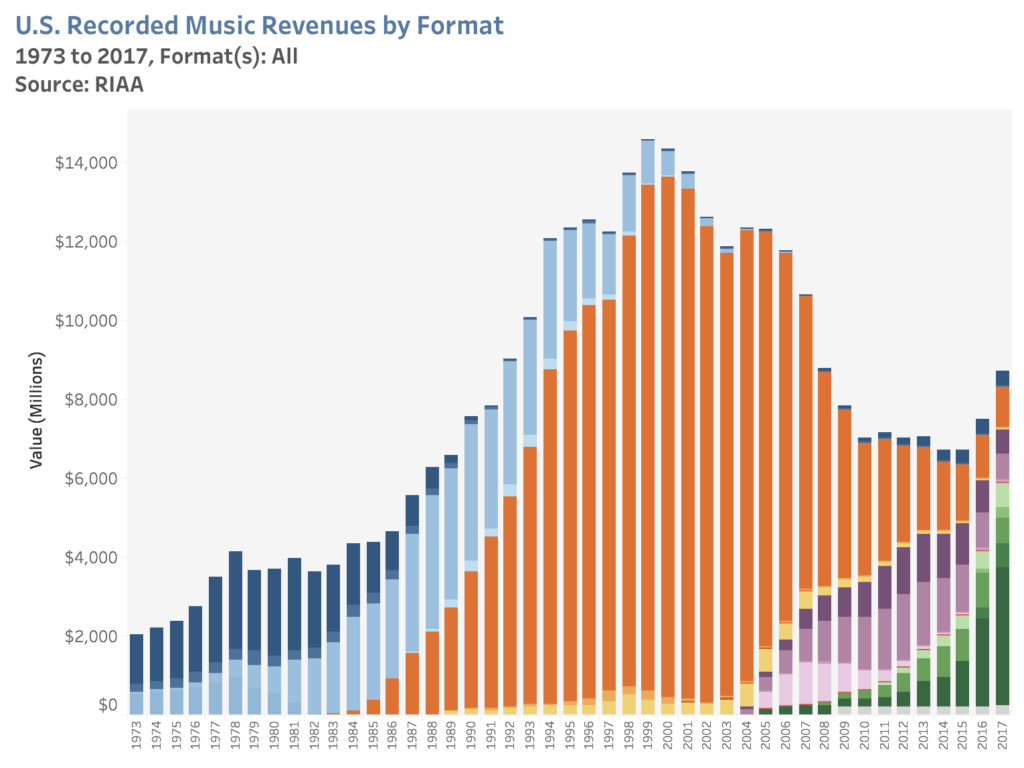

In 1999, music industry revenue in the United States peaked at $14.6 billion (all numbers are from the RIAA). It is important to be precise, though, about what was being sold:

- $12.8 billion was from the sale of CDs

- $1.1 billion was from the sale of cassettes

- $378 million was from the sale of music videos on physical media

- $222.4 million was from the sale of CD singles

In short, the music industry was primarily selling plastic discs in jewel cases; the music encoded on those discs was a means of differentiating those pieces of plastic from other ones, but music itself was not being sold.

This may sounds like a stupid distinction, but it explains what happened after that peak:

Music industry revenue plummeted, even as the distribution and availability of music skyrocketed: the issue is that people were no longer buying plastic discs, which is what the music industry was selling; they were simply downloading music directly.

Selling Convenience

The problem is that recorded music has always been worthless: once a recording is made, it can be copied endlessly, which means the supply is effectively infinite; it follows that to capture value from a recording depends on the imposition of scarcity. That is exactly what plastic discs were: a finite supply of a physical good differentiated by their being the most convenient way to get music. Pirating MP3s from sites like Napster or its descendants, though, was even more convenient — and cheaper.

As you can see from the chart, the industry started to stabilize in 2010, and in 2016 returned to growth; 2018 looks to be up around 10% from 2017’s $8.7 billion number, and it seems likely the industry will pass that 1999 peak in the not-too-distant future.

What happened is that the music industry — prodded in large part by Spotify, and then Apple — found something new to sell. No, they are still not selling music; in fact, they are beating piracy at its own game: the music industry is selling convenience. Get nearly any piece of recorded music ever made, for a mere $10/month.

I don’t agree with some aspects of his analysis of open source in the rest of the article, but Thompson’s introductory framing is brilliant. Sometimes we get hung up on the thing that we think is the product in way that blinds us to the critical aspects that are valuable to the customer. These blind spots can cause us to miss potential points of instability in a seemingly stable market landscape. And cloud computing is a classic example of a thoroughly unsexy idea that can sneak into one of those blind spots. It certainly did in the LMS market.

The Instructure surprise

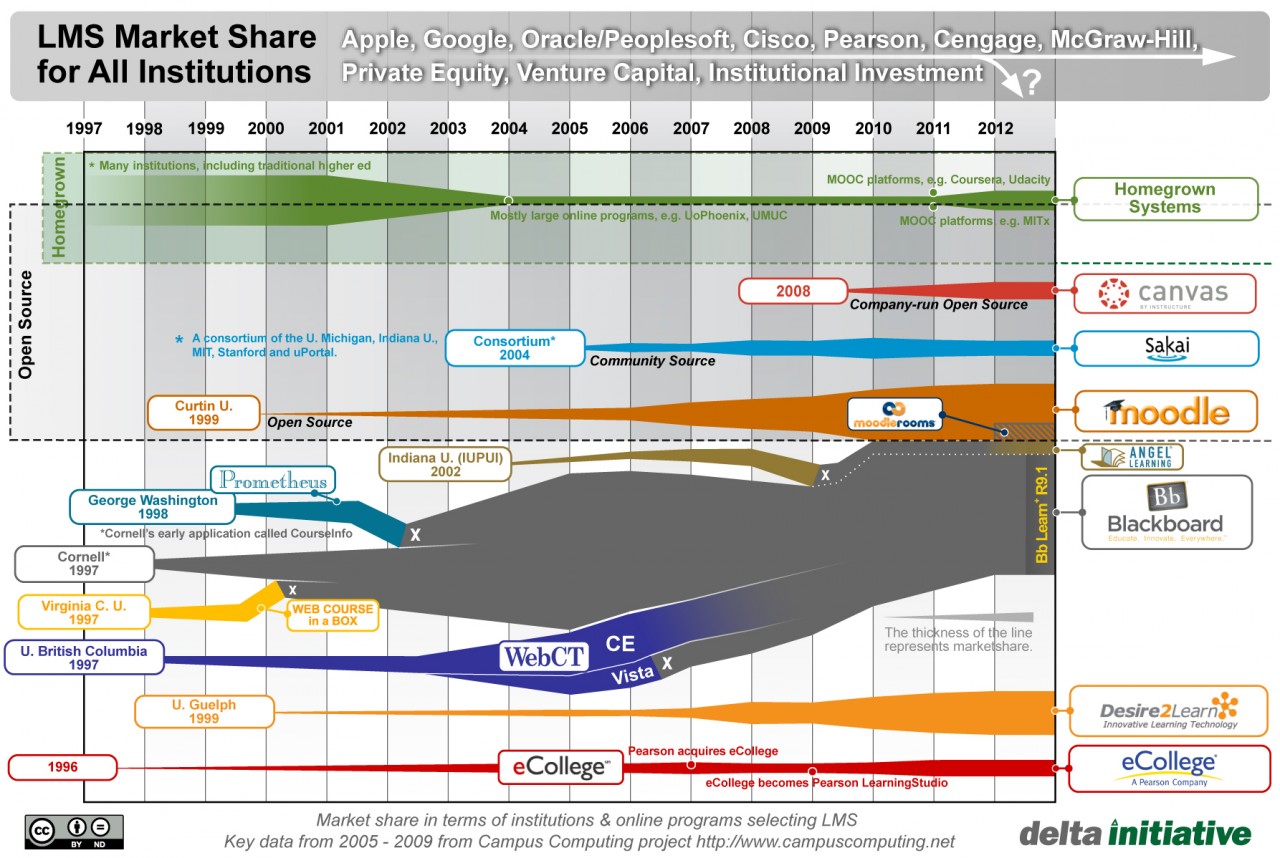

Instructure’s rise is a perfect example of one of those surprises. Let’s think back to the late Noughties, when the company was founded. This predates Phil’s coming to blog on e-Literate, so we’ll have to look at a 2009 version of his famous squid chart that he posted on the blog of his former employer:

Instructure, having been founded the year before this version of the chart was made, had not yet scored its first big deal with the Utah Education Network. They were literally not on the map. Blackboard was a juggernaut, having successfully swallowed two of their most formidable North American competitors, WebCT and ANGEL. Blackboard was also in the midst of a patent infringement case with Desire2Learn (now known as D2L), having won their case in 2008, only to lose upon appeal in mid-2009. Even after the suit was over, nobody knew how well Desire2Learn would bounce back after seeing their sales largely freeze during the year when it looked like Blackboard would win. eCollege was doing…fine, but it was serving the niches of for-profits and small schools, and there was no real sign that it was going to break out into the general market.

The real action in 2009 appeared to be in open source. Moodle, having picked up the smaller customers that Blackboard had deliberately driven away because of their low profitability, was beginning to score bigger wins. The change was most visible in the Cal State system, where Moodle was spreading there like a virus. Sakai’s growth by institutional adoption numbers was not nearly as dramatic, but in contrast to Moodle, they were rich in prestigious R1 university adopters. In 2005, when I was working at SUNY, I remember my boss at the time telling me, “They have MIT, Stanford, Michigan, Indiana…they can’t fail!” There was a widespread feeling among academics that the only way to escape being a Blackboard hostage…er…customer was to run an open source LMS that the company couldn’t buy. (Blackboard didn’t acquire the largest Moodle hosting provider in the United States until 2012.) It felt like the battle was going to be between Blackboard and open source.

Two years later, Phil’s squid diagram in his inaugural e-Literate post wasn’t much different:

You can see at the top of the diagram that there was increasing speculation about whether other companies—mostly big, established ones—might enter the market. There were, as always, a few startups that popped up in that time period, only to fade away, either by dying or by pivoting. (Remember Epsilen?) But by and large, the fight continued to be perceived as Blackboard vs. Open Source, with D2L and eCollege—by then rebranded by Pearson as LearningStudio—doing fine but not setting the world on fire. Instructure is still not yet on Phil’s map. We had noticed Instructure and written a few posts about them, but honestly, neither of us thought that a new proprietary entrant could break its way into the market, particularly if it lacked the muscle of a big player like a major SIS vendor or textbook publisher.

But by 2013, the picture had changed:

Canvas was growing. Fast. Here’s the squid diagram a year later:

Look at that Canvas line.

Whoah.

It was really only in 2013 and 2014 that most of us started to realize that Canvas was not only going to survive but might provide significant competition to the incumbents. Why did it take us so long to see it coming?

I would argue that we undervalued three of Instructure’s core strengths: usability, customer service, and reliability. We’ve written here before about how Instructure’s usability was a step function better than its competitors at the time. The early but seminal example was Speed Grader, Canvas’ grading app that greatly increased ease of use of the grading function and was the first mobile LMS app that demonstrated the potential of tablet computing. Blogs and wikis, which LMS providers had begun to add, only to find them barely used, were not considered valuable by most faculty. Giving them back hours of their time that they would have spent entering grades, on the other hand…. Likewise, we’ve written about how Instructure quickly established itself as the “uncola” of LMS companies by providing excellent customer service that was inextricably tied with their “not-Blackboard, not-Oracle” brand identity. Both of these non-features turned out to be more valuable to many customers than the bazillion features that were beginning to encrust the older, more “mature” LMSs.

But at least usability, customer service, and branding are all visible to end users in some tangible sense. In contrast, cloud computing was most valuable for something that it made invisible. Specifically, downtime. By 2012, the LMS had become a mission-critical application. Online learning was in full swing. For-profit universities like the University of Phoenix as well as public (mostly Sloan Consortium-funded) public universities like University of Maryland, University College (UMUC) had reached impressive scale in around 2008, right when Instructure was being born. In the intervening four-year period, many colleges and universities were chasing that scale. In 2010, Western Governors University founded its first offshoot campus in Indiana. The Online Program Management (OPM) business was hitting its stride. Academic Partnerships and 2U, two of the most successful OPM companies, were both founded the same year as Instructure. By 2012, both were surging. (Forbes named 2U one of the “10 startups changing the world” that year.)

And online usage in general was surging. Gmail exited beta in 2009. The two remarkable aspects about Gmail were that it provided full, intuitive functionality in any browser and it never went down. Not for crashes, and not for upgrades. It was just always there. Occasionally you would log in and there would be a new feature. But most of those upgrades were invisible to the user. A friend of mine used to love to ask a question during this period to make this exact point: “What version of Google are you using?” Not having to know your version number, having the software be always there and always up-to-date, turned out to be a killer capability. The most important feature turned out to be the one that you never noticed, because it turned your app into something that end users could come to take for granted. As more people were using rich web-based applications—remember “Web 2.0”?—they started having higher expectations for online usage in general. If buying stuff online became a normal, everyday thing, then why wouldn’t checking your course grades online? Even in a traditional, face-to-face classroom, students were starting to expect the convenience of the web to just be there for them in their classes. Documents should be there. Announcements should be there. Schedules should be there. Grades should be there. All the time. Increasingly, when the LMS went down, it was like the ATM machines going down. Before ATMs existed, life went on. Nobody died without them. Nobody noticed the lack of convenience. But afterward, since people have grown to take them for granted, any outage is an outrage.

I honestly didn’t understand why Instructure was making such a big deal about the cloud when they first launched. Neither did their competitors. And it took them quite a long time to figure it out.

Blackboard’s Hopes

Let’s fast-forward now to the relatively recent 2017 version of the squid diagram:1

It’s a different world. Sakai and Moodle, having peaked at slightly different points, are in decline in US and Canadian higher education. Canvas’ growth has been off the charts, and has only really slowed down in the year since this chart was made, as LMS adoptions in general have slowed in this market. D2L’s Brightspace bounced back after the patent suit and is holding their own.

But the biggest change is that Blackboard, far from being dominant, is a shadow of its former self in terms of its share of this market. These days, their press releases about customer “wins” in the United States are about Blackboard customers who decide not to leave after conducting an evaluation. We’re not seeing new customer wins in this market.

One of the reasons that we’ve been arguing that SaaS adoption is more important to Blackboard than adoption of its new(er) Ultra user experience right now is for the same reason that SaaS was so important to Instructure. The most important feature for Blackboard right now is the one that the end user doesn’t see. LMS migrations may be easier than they used to be, but they still require significant time and, often, pain on the part of the users who experience the transition. Most of Blackboard’s most risk-tolerant customers have already migrated to a newer, shinier alternative. The company’s remaining North American customer base is heavily risk-averse. It’s exactly that risk aversion that makes SaaS attractive. Blackboard is saying to these customers, essentially,

Hey, migrating is hard. Why don’t you just switch to SaaS? It can be invisible to your end users if you want it to be, but you won’t be in the firing line anymore with the painful downtime that you always get blamed for. And once you’re on SaaS, you can try out Ultra at your own pace. If the change is too scary, then don’t worry. You don’t have to make it. If you want to try it, slow or fast, with a few classes or with all of them, you’re in control. But let’s get rid of that pesky downtime for you. And let’s make upgrades less painful too. Just sign here to extend your contract for a few years and we’ll make those nasty surprises go away for your stakeholders.

It’s the SaaS, rather than Ultra, that is the primary driver for contract extensions. Which is likely why the company’s latest “Hey, we’re doing great!” press release was entitled “SaaS Deployment of Blackboard Learn Continues to Gain Momentum Around the World” rather than “Ultra Deployment of Blackboard Learn Continues to Gain Momentum Around the World” even though both headlines could equally fit the text of the press release. If Ultra adoption creeps along for another couple of years, it probably wouldn’t hurt Blackboard too badly. But if SaaS adoption creeps along, that would be a lot more serious.

Moodle’s worries

The SaaS shoe is on the other foot for Blackboard when it comes to Moodle. While the company has been playing catch-up to Instructure with their 3-year-old SaaS Learn offering, they are doing to Moodle something like what Instructure did to them with their Blackboard Open LMS offering. When Moodlerooms, which was the largest Moodle hosting provider in the US, was acquired by Blackboard in 2012, they had already built out a highly scalable SaaS version of Moodle. (In fact, Blackboard Learn’s SaaS architecture is based on lessons the company learned from studying the Moodlerooms SaaS architecture.) In global higher education markets outside of North America, Moodle is still a formidable player. In fact, it is the dominant player in many places. But the core open source Moodle project has been slow to roll out true multi-tenant SaaS capabilities. This has created an opportunity for Blackboard to roll into markets that are heavily saturated with self-hosted Moodle and say, essentially,

Hey, moving is hard. Why don’t you just switch to our Moodle-based SaaS LMS? It can be invisible to your end users if you want it to be, but you won’t be in the firing line anymore with the painful downtime that you always get blamed for. And once you’re on SaaS, you can try out our enhancements at your own pace. If the change is too scary, then don’t worry. You don’t have to make it. But if you want to try it, slow or fast, with a few classes or with all of them, you’re in control. But let’s get rid of that pesky downtime for you. And the upgrade cycles. Just sign here to have us get you on an Open LMS contract and we’ll make those nasty surprises go away for your stakeholders.

Those self-hosted Moodle customers that aren’t moving to Blackboard’s Open LMS are generally moving to…wait for it…the SaaS versions of Blackboard Learn, Instructure Canvas, or D2L Brightspace. Self-hosting as an option is fading away in the LMS market, for the same reason that fewer and fewer organizations are hosting their own email servers. The market has apparently decided that self-hosting these applications brings them a lot of pain without a lot of gain. And they may be willing to trade off functionality and autonomy in return for the perceived reliability that comes with SaaS.

This brings us full circle to Ben Thompson’s blog post about Amazon and Mongo DB. Amazon basically built its own database that runs natively on the company’s cloud platform and implements an older version of Mongo’s APIs. The threat to Mongo is that customers will find Amazon’s hey-it-just-works offering to be more attractive than Mongo’s more up-to-date APIs or than any benefits, either ideological or practical, that come from adopting open source. We don’t know how this will play out with Amazon and Mongo yet, but we’ve certainly seen how it has played out (and continues to play out) in the LMS market. It’s easy to get distracted by shiny feature-driven trends like competency-based learning, adaptive learning, or learning relationship management. These may or may not turn out to be important. But if you undervalue the boring and often invisible product attributes of “easy” and “reliable,” you can easily miss a sharp turn in the road.

- It’s worth remembering that these diagrams are of market share for the US and Canada only. [↩]

Great analysis. I agree Saas is driving the need to change. Unfortunately, moving blackboard from hosted, or even managed hosted, to Saas still takes blackboard 4 days of downtime. At that point, Canvas is an easier sell to a campus.

I always enjoy a trip down memory lane…

I’d add TIMING as a key factor.

I joined and co-built eCollege’s offering starting in 1996. Largely due to our (mine, I suppose) decision to partner with Microsoft and use their stuff, we didn’t have an easy way to offer our solution on premises. So we were “cloud only” Saas from day 1.

So we dangled the same carrot: less headache! less downtime! less maintenance! no versions to worry about!

This was, for many at the time, inconceivable. Our school data would live outside our campus? On some vendor system? Pure blasphemy, with legal hurdles and so on.

In my opinion this was a contributing factor towards Blackboard’s faster growth as well as eCollege’s slant towards for-profits (whose mindsets were a bit more accommodating to the idea of cloud hosting).

The market was simply not ready at that time. Instructure nailed it in the late 2000’s when minds started to change.

There’s an interesting analogy in the email market. It would be great if someone had real data, but here’s what I’m seeing. The growth in campus adoptions of Gmail was driven, not exclusively but largely, by the SaaS model. Now that Microsoft has a competitive product with Office 365, they are recapturing market share from Google. Once everything is SaaS, other decision criteria become more important.

Having been part of the Utah Education Network early adoption of Canvas (all higher ed schools and trade techs in Utah) in 2011, I can tell you that this is spot on with what I witnessed and was part of. At this time many were skeptical about SaaS, and gave every reason why schools would “loose control” of their LMS destiny if they did not host prem. I think there are probably a few schools who still have that reason. One other factor was that early on, Bb execs downplayed the possibility of a threat from Canvas. They felt Bb was too big to fall/fail, did not take the potential seriously. And just like that we are in 2019. Well written article!

David, from our preliminary analysis, it looks like Blackboard has converted very roughly 25% of its higher education customers to SaaS, which is sort of a “slow and steady” performance. We’ve seen a slowing of RFPs in general, which may or may not be a short-term thing. So I’d say the jury is still out on their strategy.

Brad, good point about eCollege and timing. There’s no question that we experienced a sea change in the attitudes toward external hosting in general right around the time that Instructure hit the market.

Michael, there’s little doubt that we will get to the point where SaaS is a given and will become table stakes rather than differentiating. But we’re not quite there yet in the US LMS market, and we’re not even close yet in most international markets.