Moodle News responded to our recent coverage regarding the platform’s declining market share by pushing back hard with an article that simultaneously insinuates bias on our part and attempts to use our numbers to draw the opposite conclusions from the ones that we have put forward. This presented us with something of a dilemma. As professional analysts, we try very hard to be undefensive when we are critiqued. If people think we are biased, they are entitled to their opinions. If people question our data or analysis, we try to respond only if we think their critique of us has merit. If we don’t think it does, we generally let our original work speak for itself unless we have a specific reason to do otherwise. So, from this perspective, our default editorial position is to let Moodle News have their say and leave it alone. I will add that our overall impression of Moodle News has been that it is generally a fair and thoughtful outlet. We have no particular desire to pick a fight with them.

On the other hand, we are not just analysts. One of the more common compliments we get from people who trust our work is that they believe it is animated by a concern for improving education. I take these comments to mean more than just that we “care” in some abstract sense. Rather, they seem to be saying that our choices of what stories we cover and how we cover them are animated by our desire for our analysis to be a tool for educators to help improve education. From that perspective, it’s hard for me personally to let the Moodle News story go unanswered. I care about what happens to Moodle, not so much because I care about Moodle in and of itself but because I care about the good that the platform and the community do for education across the globe.

Sometimes when we poke at a group because of a problem, it’s partly because we want to call their attention to it in the hopes that they fix it. If we poke harder, it may be because we’re not convinced that they’re paying attention to the dangers that we see. (See, for example, Phil’s recent Unizin coverage.)

Beyond the Moodle News piece and the occasional (but energetic) challenges we get from Moodle advocates when we present our numbers at conferences, the case for poking here is bolstered by Martin Dougiamas’ periodic public questioning of our analysis, including his comment on that aforementioned last post. The bulk of that comment was as follows:

I get that you are a fan of certain companies and that is fine, but I don’t understand the highly negative and uninformed spin from you lately. Look at the title of this article! These feel like intentional attacks, to be honest, and I have to wonder why.

The fact is your entire article here is based on the false supposition that our business model is a) static and b) based entirely on higher ed. However, we already have a number of new and exciting initiatives that you clearly don’t know about (MoodleCloud, MoodleNet, LearnMoodle, MoodleServices as well as new things not announced yet) that are supporting our current and future growth.

Sustainability of Open Source and all Open initiatives is something we care about deeply and is part of everything we do.

Again, readers have to come to their own conclusions regarding the quality of and motivations for our posts. From our perspective, we tend to write negative headlines when we see negative news. We tend to get more negative in our tone when we think the people we are trying to reach are not hearing us (or are not honest, though that is not an accusation that I am making here).

As somebody who has been very directly involved with and committed to open source projects myself, I have learned that the very passion which drives participation can also cause advocates to dismiss any bad news as “fake news.” This can be fatal to a project. Moodle has massive market share, a fresh infusion of cash, and plenty of talent. There is time to address any challenges that the project faces. But only if those challenges are faced.

I have decided to take one more run at this topic because I would like to see the Moodle community succeed, and in order to do that, I believe it will have to grapple with challenges that I don’t see evidence that it is fully grappling with yet.

The Passion Play of Open Source in Crisis

While the role I have chosen for myself in the ed tech ecosystem has required me to be ecumenical in recent years, I had previously been an active participant in two different open source LMS projects. The first was a system called dotLRN, which came into existence around 2000 and seems to have died around 2010. (The web site is still up, but nobody appears to be home.) From a functional perspective, dotLRN was fantastic. In retrospect, it was a decade ahead of its competition in a number of ways. But its technology stack was quirky. It was written in a programming language called TCL—which stands for “tool command language” but is referred to by its proponents as “tickle”—and ran on top of an early open source application server called AOLServer. I was told by people I trusted that these were perfectly valid technical choices that had distinct advantages over contemporary alternatives. As a newbie to software development and a non-engineer, I had no reason to doubt those assessments.

But while I didn’t know much about technology, I did know how to listen. Over time, it became clear to me that attracting new developers and winning the confidence of university IT departments would be hard. Nobody seemed to think that learning a programming language called “tickle” and an application server called “AOLServer” seemed like a path to a career on the cutting edge. I grew more confident in that assessment as it became clear that adoption growth of the platform had hit a wall and it wasn’t even getting considered as an option in most cases. I raised this concern with the community, but many of the engineers continued to insist that the superiority of their choices would win in the end. And they could point to all the strengths of their platform relative to the competition as evidence for their case.

The problem came to a head one day for me when I made a discovery about one of those strengths. There was a situation—I’ve long since forgotten the details—where the dotLRN developers decided to turn one of the capabilities of the platform into a web service. I asked, “How hard was that to do?” The answer? “Trivial. It’s just configuration. We can turn pretty much any API call into a web service with the flip of a switch.”

I was stunned. This seemed like the way out! Let the dotLRN core continue to be developed by a limited number of specialized engineers, similarly to how web servers like Apache were being written in C by a small number of hard-core specialized developers. Develop a new front end using a more popular language, which at that time would have likely been PHP, Python, or Java. Use web services to communicate between the two. This was before REST and JSON had really hit the scene, so they would have been XML-based web services. But the point was, nobody would have to learn TCL. It would change everything, I thought.

The dotLRN developer community was less enthusiastic. They believed their development approach was technically superior. Why should they pander to the least common denominator by promoting an awful, inelegant language like PHP? Besides, they had a huge installation in Brazil. Things were looking up, they said.

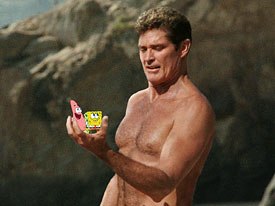

It turns out that many open source communities, when faced with declining adoption that is forcing consideration of unpalatable choices, become some version of David Hasslehoff. “I may be the butt of jokes in the US, but I’m huge in Germany!” That is a bad place to be. Before you know it, the only things people remember you for are your deeply unfortunate “drunken stupor” YouTube video and your cameo in the SpongeBob movie.

Could a switch to web services have saved dotLRN? I don’t know. It would have been tough no matter what. But the point is that open source communities are often driven by the passion of the participants. While it was exactly that commitment to the mission that attracted me to dotLRN at a time when the proprietary alternatives made me very queasy, it was that very same emotion that blinded some of the most passionate and committed community members to problems that turned out to be existential.

When I left the dotLRN community, it was in the process of tearing itself apart. There was a lot of internal debate about whether anything needed to be done for the health of the project and, if so, what. One particularly bright and charismatic young leader in the community became offended that there was resistance to the direction that he (and his company) wanted to take dotLRN. So he left. (I hear he has since gone on to do great work under the auspices of the Mozilla community.) There was a sense among the remaining members that their suffering was externally inflicted. How could the world fail to appreciate the wonderful things that they had built and shared for everyone’s benefit? They were the victims, sacrificed by the unappreciative mob as thanks for their self-sacrificing effort. And now….

I have seen similar challenges, albeit to a much lesser degree, in the Sakai community. By and large, that community has a more realistic grasp of where their challenges are and what their niche is. They also appear to be fairly stable at the moment.

But passion can blind the Sakai community members from time to time too. (“We’re big in Spain!”) I can remember a time not too many years ago when people in that community—smart people who I respect and whose livelihoods depended on the health of the platform—who thought everything was just fine. One in particular told me that all Sakai needed was a refresh of the grade book and the test engine. Otherwise, everything was just great. (I’m not sure whether this was before or after Sakai finally fixed a fundamental problem where the platform broke the browser back button, but if it was after, it wasn’t long after.)

That guy is now the CTO for a company that is not Sakai-focused.

More recently, the last time I was at an Apereo conference, I attended a session whose abstract said the presenters would talk about how they welcome RFP processes and have kept Sakai competitive at their schools. I was curious. What followed was a litany of the presenters raising every imaginable obstacle to choosing Sakai over competitors, including many reasonable ones, and off-handledly dismissed them one by one. Perhaps inevitably, they came around to Phil’s squid diagram. They clearly didn’t know either that I was connected to the graph or that I had previously served on the Sakai Foundation Board of Directors. I didn’t say anything; I hadn’t gone to the session to ambush the poor guys. But others in the room knew who I was. All eyes turned to me, and several people pointed to me. The guy presenting in the moment rehearsed his arguments.

”That graph is based on old data, right?”

No, you just have an old version. The latest version is up on the blog, and it doesn’t look any better.

”But this is just a small sample.”

About 90% of US and Canadian institutions.

You get the idea.

No organization can remain healthy and effective if it doesn’t balance its passion with a healthy dose of skepticism and self-reflection.

Which brings us to the Moodle News piece.

Getting the Numbers Right

There appear to be three sources of misunderstanding in the article in question. The first is not understanding our point about the intersecting trends of the collapse of new implementations (meaning very few new schools choosing to adopt Moodle in a particular year) with an increase in decommissions (meaning more schools replacing Moodle with another LMS). In North American higher education, we are already seeing a decline in total Moodle institutions of 45 – 50 (depending on when you measure). This is roughly equal to the 1% rounding number that we mentioned in the post (i.e., 1% of 4,500+ institutions in North America dataset).

The Moodle News author is correct in noting that for the horse race view, Blackboard and Moodle are closer than ever when measured by percentage of institutions using as primary system. However, this is mainly because Blackboard’s market share has collapsed much faster than Moodle’s. Arguing that this shows Moodle is strong is a little bit like arguing that MySpace is strong because it has surpassed Napster’s market share (though I will grant that a slow decline is better than a fast one).

The second problem is in not understanding the difference between new implementations and installed base. The chart I referenced in my last Moodle post measures the percentage of new implementations in each year moving towards Moodle – this is where (at the time of article) 0% of 2017 new implementations went to Moodle, 55% went to Canvas, and 44% to D2L. (To be fair, we’ve detected a few new implementations since that last piece; we will include them in our next periodic update of the graphs.)

All of which leaves us to wonder: How can an LMS have no growth while its close competitors show increases of 55% and 44% (for D2L, now with a 15% market share), and end the year with its market share unchanged?

Market share is based on installed base—the percentage of institutions having a particular LMS as its primary system as measured in a point of time. To get this number, we add new implementations, subtract decommissions, account for the changing denominator in the total number of institutions (there are a lot of consolidation and closings happening in the US), and round to the nearest whole percentage.

So the answer to the author’s question is that Moodle has lost 45 – 50 net institutions in North American higher education. In other words, roughly equal to the 1% rounding number.

The third problem is not understanding the difference between primary institutional adoptions, which is the measure that we use in our analysis, and the measure of the number of registered sites in Moodle.org’s stats. We don’t, for example, count the sites that may be self-run by an individual professor or department and that may be registered with Moodle.org. The latter may be important to the community from a mission perspective, but those adoptions do not impact the financial resources available for development of the platform. You can’t combine the two numbers.

Speaking of which, the situation looks even worse for Moodle the closer we get to counting things that directly translate into revenues. The numbers that we track in many of our charts and graphs are the numbers of institutions that adopt different platforms. But the numbers that really matter for the financial health with most of these platforms is the number of students, because institutions pay their vendors, including the Moodle Partners that bankroll Moodle HQ, by the enrollment. For example, Southern New Hampshire University (which is moving to D2L) and Glendale Career College (which is on Moodle) each count as one institutional customer. But SNHU has over 100,000 students, while GCC has 300.

When measuring by numbers of students, Moodle is fourth in the US and Canada, behind Blackboard Learn, Canvas, and Brightspace—and these numbers do not include future losses from the University of Minnesota and other schools that have chosen to migrate off of Moodle in the near future. Note the numbers in the right-most column of this chart:

A Healthy Skepticism of Skepticism

Is it possible that we at e-Literate are biased against Moodle? Of course it is. While we try our best to be objective, we are humans, and humans can be biased. The Moodle News author spends a fair bit of energy insinuating that we have a preference for other platforms. I’m not going to address that question, partly because I’m not the best judge of my own biases and partly because it’s not the question that Moodle advocates should be asking. Rather, the main question they should be worried about and should be investigating with as much absence of bias as they can muster, is the following:

Is e-Literate’s analysis true?

Could we be wrong? Of course we could. I very much doubt that we are off by much in the US and Canada, where we our data are the strongest. The margin of error increases as we get to parts of the world where our coverage is less complete (or, in some cases, non-existent). Those areas should be clear—and, in fact, are referenced in the Moodle News article—because we quantify the data fidelity in our regional analyses. If Moodle is huge in Germany, or China, or Myanmar, we might not be picking that up in our data.

There is one person who may well have better data than we have, and Moodle advocates have reason to believe that he is not biased against Moodle. His name is Martin Dougiamas. He argued in the comment quoted at the top of the post that we don’t really understand or have visibility into the business model of Moodle Pty. If that is true, then we would like to be enlightened. And the Moodle community should want that too, for peace of mind.

Moodle Pty could provide the community with two kinds of information that would help its advocates understand how much they should be worried (or not). First, Moodle Partners likely give Moodle Pty counts of customers by institution and numbers of students. (I don’t know this for certain, but I’m not sure how Moodle Pty could verify that they are being properly paid by the partner without this information.) The company could publish this information, aggregated by country so that individual customers and partners have some degree of anonymity while still giving the community a sense of the inputs that fund Moodle development. A second disclosure that Moodle Pty could offer is direct revenue numbers that are transparent enough for community members and other interested parties to independently verify the company’s financial health. While Moodle Pty is not legally obligated to provide any of these numbers, there are disclosure models in both non-profit foundations and for-profit companies that the company could choose to follow. At the moment, the status of Moodle Pty as a private corporation shields it from transparency requirements of either non-profit foundations or publicly traded corporations. But that doesn’t mean that the company, as the main engine of sustainability for a huge open source project that, despite current growth challenges, remains by far the world’s most widely adopted academic LMS, couldn’t or shouldn’t choose to be transparent about numbers that are critical to the project’s sustainability.

If Moodle News really wants to check our numbers, then they should be asking Moodle Pty for adoption numbers of Moodle Partner-supported installations by institution, headcount, and/or revenues. And their biggest concern, as Moodle advocates, should not be whether some US analysts are talking smack about their favorite platform. It should be about how healthy and sustainable that platform truly is.

You brought up the the U of Minnesota move from a self hosted Moodle system to a Saas Canvas. Is that really somethng that Moodle Pty needs to worry about? I don’t have any direct connection to anyone in the know about how that decision went down, but I have lots of indirect connections. I’ve heard the decision to move to Canvas was essentially a done deal as soon as the U of Mn signed on to Unizin. From what I can tell, no Moodle Partner tried very hard to get that deal. Moodle will probably lose some users with the U of Mn going to Canvas, but were those paying users?

Tracking the success of the switch from Moodle to Canvas at the U of MN will be instructive. I’m not convinced, though, that it’s something that Moodle Pty or other Moodle users needs to worry much about. The big news here is the the U of MN went from self-hosted to Saas. Going to a different Saas provider, or a Saas Moodle Partner, a few years down the road won’t be as big a deal. In the meantime, Canvas has a bunch of new customers to keep happy, and the U of Mn has bunch of LMS support staff to re-deploy, or something.

In and of itself, UMn doesn’t represent a loss of revenue to Moodle Pty (as far as I know). But it is consistent with two trends we’ve been observing that should be of concern. First, larger universities are defecting from Moodle. They could convert to SaaS Moodle—a point that’s relevant to your question on the previous post—but they’re not. This leads to a second trend, which is of larger concern. The pattern we’re seeing, which we don’t yet have enough data to confirm with a high degree of confidence but which we see more and more signs of in different regions, is that when self-hosted Moodle institutions change, they do not change to Moodle Partner-hosted Moodle.

If Moodle is going to maintain healthy revenues for ongoing development, they’re probably going to have to stop and, eventually, reverse this trend (or else build out some strong and stable alternate sources of revenue).

I was a few seats down from you at that Open Apereo 2016 session in NYC. I certainly looked your way, but I didn’t point. I think you handled yourself well and you handled the presenters well and appreciated that they didn’t begin their presentation with the intent to pick a fight with their audience.

As that “The Advocacy, Defense, and Evangelization of Sakai” presentation went on I struggled to understand what the motives of the presenters were. The presenters didn’t have a frequent association with the Sakai community, so I did not know what to anticipate. I expected an argument on control of destiny, value for money and opportunity for innovation – there was some of that, but that presentation struck me as strategies to preserve status quo for it’s sake. And then the squid diagram came up…

In any case, Apereo benefits from being community around academic open source where different perspectives interact and learn from each other. I hope that was the outcome of that session.

Matt, thanks for that independent read of that session. I was and am a big proponent of the merger that created the Apereo Foundation for precisely the reason that you give here. The community is now bigger than any one project, which changes the contexts of the conversations in ways that change the larger meaning of them. So, to your point, people from different open source projects have an opportunity to learn from each other. That includes watching their colleagues struggle to balance passion with objectivity at a enough of an emotional distance to make it a more useful learning experience.

Michael F., I find this analysis interesting, but I tend to scrutinize graphs without seeing the data behind them. Can you provide open access to the raw-data used to create the graphs, “% of New LMS Implementations Each Year in the U.S. and Canada” and “LMS Market Share for U.S. and Canadian Higher Ed Institutions.”?

Sorry, Michael, we don’t give out raw data dumps. Our data partner, LISTedTECH, builds their business on their collection methodology, so giving away their data would be giving away their business. If you have specific validation questions, we might be able to find a way to help you without giving away our partner’s business.

For what it’s worth, the market numbers for the North American market found by Edutechnica, which uses a different data-gathering methodology, are not too far off from ours. Since there really isn’t any fancy statistical analysis going on behind the scenes on these graphs, it really is mostly a question of defining what counts as an institutional LMS and then finding a way to keep a current count.

I’ll add that you can read more about our data-gathering methodology here: https://eliterate.us/note-data-used-lms-market-analysis/

Thanks Michael F.,

Another question regarding data counting for market share %’s. If an institution is migrating from LMS A to LMS B over a period of 2 years, would the LMS numbers for LMS A decrease and LMS B increase at the beginning of the 2 year period or would LMS A have no decrease until the complete decommission?

Trying to gauge the percentage completion of a transition in progress would go beyond the data that we have. We have a commission date for the new system and a decommission date for the old one. When there is an overlap between the two, count both until the old system is decommissioned.